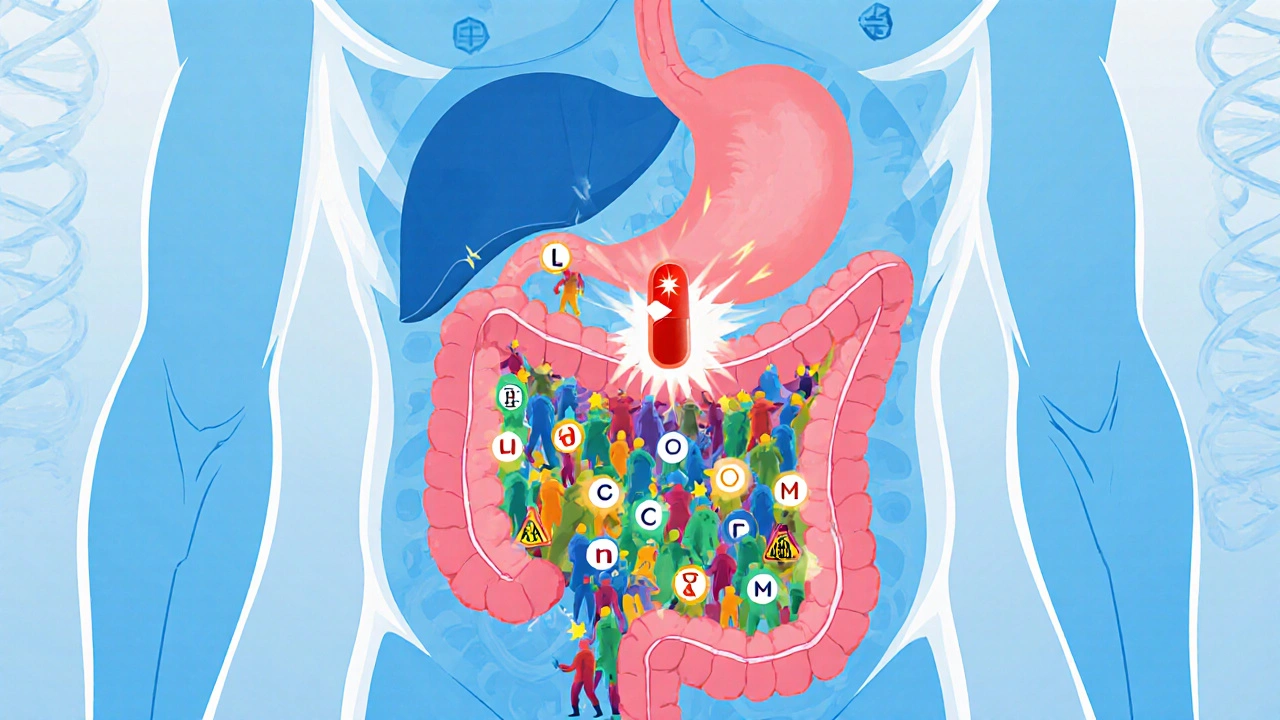

Every time you take a pill, your gut bacteria are already working on it-often in ways doctors never expected. What you think is just your body processing medication? It’s actually a team of trillions of microbes doing their own chemistry, turning drugs into something stronger, weaker, or even toxic. This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now in millions of people, and it’s the reason why two people taking the same drug at the same dose can have wildly different outcomes-one feels relief, the other ends up in the ER.

Why Your Gut Is a Hidden Drug Factory

Your gut isn’t just a tube for digestion. It’s home to over 100 trillion bacteria, viruses, and fungi, packed into a space smaller than a soccer ball. These microbes aren’t just along for the ride-they’re active participants in how your body handles medicine. They have enzymes that human cells don’t. And they use them to break down, rebuild, or activate drugs in ways that completely change how they work. Take irinotecan, a chemotherapy drug used for colon cancer. It’s designed to kill cancer cells, but in about one in three patients, it causes severe, sometimes life-threatening diarrhea. Why? Because gut bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme reactivates a harmless metabolite of the drug back into its toxic form, SN-38, right inside the intestines. Studies show that patients with higher levels of this enzyme have up to 87% more severe diarrhea. It’s not the drug failing-it’s the microbiome turning it into a problem. The same thing happens with digoxin, a heart medication. For decades, doctors couldn’t explain why some patients needed much higher doses than others. Turns out, a specific bacterium called Eggerthella lenta is a gut microbe that breaks down digoxin into an inactive form. Only people with this bacterium in their gut need higher doses. Without it, the drug stays active and can cause dangerous side effects.From Prodrugs to Poison: How Bacteria Change Drugs

Some drugs are designed to be inactive until they’re activated in the body. These are called prodrugs. But here’s the twist: sometimes, your gut bacteria are the ones that activate them-not your liver. Prontosil, one of the first antibiotics ever developed, only works because gut bacteria cut it apart to release sulfanilamide, the real active ingredient. In mice treated with antibiotics, prontosil’s effectiveness dropped from 90% to just 12%. That means if you’re on a course of antibiotics and take a prodrug, it might not work at all. On the flip side, bacteria can turn safe drugs into toxins. In a landmark 2019 study from Yale, researchers found that gut microbes were responsible for 20% to 80% of toxic metabolites in three different drugs. One antiviral drug, for example, produced 73% of its toxic byproducts through bacterial action. That’s not a side effect of the drug-it’s a side effect of your microbiome. Even common medications like clonazepam, used for anxiety and seizures, behave differently in people with different gut bacteria. In germ-free mice (those raised without any microbes), clonazepam levels in the blood were 40-60% higher than in normal mice. That means your gut microbes are constantly dialing up or down the strength of your meds.Antibiotics Aren’t Just Killing Bad Bugs

When you take an antibiotic, you’re not just targeting the infection. You’re wiping out entire communities of bacteria that help metabolize your other drugs. And that can have serious consequences. A 2014 study showed that long-term antibiotic use reduced the effectiveness of lovastatin, a cholesterol-lowering drug, by 35%. Why? Because the bacteria that normally help break down statins were gone. Without them, the drug didn’t get processed the way it should, and cholesterol levels didn’t drop as expected. Even worse, antibiotics can make some drugs more dangerous. In rodent studies, treating animals with antibiotics before giving them nitrazepam (a sedative) reduced birth defects by 78%. That’s because the bacteria that turned nitrazepam into a teratogen were wiped out. In humans, this could mean that a pregnant woman on antibiotics might avoid a serious fetal risk-but only if her microbiome was the cause in the first place. The problem? We don’t test for this. Doctors don’t ask what antibiotics you’ve taken in the last six months. They don’t check your microbiome before prescribing. And yet, these interactions are real, measurable, and life-altering.

What This Means for You

If you’ve ever been told, “This drug didn’t work for me,” or “You’re unusually sensitive to this,” your gut might be the reason. The same dose that helps your neighbor could make you sick. And the same drug that works perfectly for someone else might not even be absorbed properly in your body. This isn’t about being “weird” or “difficult.” It’s biology. And it’s changing how medicine is made. Pharmaceutical companies are starting to pay attention. Pfizer and Merck now screen new drugs for microbiome interactions during early testing. Why? Because if a drug causes unexpected side effects in the real world, it can cost hundreds of millions in lawsuits, recalls, and lost trust. One study estimated that including microbiome data in early trials could prevent $500 million in post-market liabilities. For patients, this means future treatments could be tailored to your gut. Imagine a simple stool test before your next prescription. The results could tell your doctor: “Your bacteria break down this drug too fast-use a higher dose,” or “Your microbiome turns this into a toxin-pick an alternative.”What’s Being Done to Fix This

Scientists are already building tools to measure how your gut affects your meds. One approach is metagenomic sequencing. For $300-$500, you can get a full genetic profile of your gut bacteria and find out if you carry the enzymes that mess with common drugs. These tests are already being used in research clinics. Another is targeted inhibitors. For example, a drug that blocks beta-glucuronidase is in Phase II trials. If it works, it could be taken alongside chemotherapy to prevent diarrhea in 60-70% of patients. That’s not just comfort-it’s survival. Fecal transplants, once used only for C. diff infections, are now being tested to reset drug metabolism. In one small study, transplanting stool from a patient who responded well to a drug into someone who didn’t improved outcomes. It’s not magic-it’s microbiome engineering. The FDA and European Medicines Agency now recommend microbiome testing for new cancer drugs. That’s huge. It means regulators are finally acknowledging that your gut isn’t just background noise-it’s part of the drug’s mechanism.

What You Can Do Today

You can’t change your microbiome overnight. But you can be smarter about how you take meds.- If you’re on long-term antibiotics, ask your doctor if any of your other medications might be affected.

- Don’t assume a drug “didn’t work” because it’s weak-ask if your gut could be breaking it down too fast.

- If you’ve had repeated side effects from a drug, your microbiome might be the clue.

- Consider a stool test if you’re on multiple medications and have unexplained reactions.

- Avoid unnecessary antibiotics. Every course changes your microbiome for months.

The Future Is Personal

The old model of medicine-“one size fits all”-is falling apart. We now know that two people can have the same diagnosis, take the same pill, and have opposite outcomes. The difference isn’t genetics alone. It’s the microbes living inside them. By 2030, doctors will likely have microbiome profiles as routine as blood pressure readings. Dosing algorithms will adjust for your bacterial enzymes. Probiotics might be prescribed not just for digestion, but to make your drugs work better. This isn’t the future. It’s already here-in labs, in trials, in the first clinics using stool tests to guide treatment. The science is solid. The data is clear. And the patients who benefit from it? They’re the ones who asked why.Can my gut bacteria make my medication less effective?

Yes. Certain gut bacteria can break down medications before your body can use them. For example, the bacterium Eggerthella lenta inactivates digoxin, a heart drug, in about 10% of people. If you have this bacterium, you may need a higher dose. Antibiotics can also wipe out helpful bacteria that help metabolize drugs, leading to unexpected changes in effectiveness.

Do probiotics help with drug metabolism?

Some probiotics may help, but it’s complicated. Most over-the-counter probiotics don’t contain the specific strains that affect drug metabolism. However, targeted probiotics designed to block harmful bacterial enzymes (like beta-glucuronidase) are in clinical trials. These aren’t available yet, but they’re being developed to reduce side effects from chemo and other drugs.

Can a stool test tell me how my gut affects my meds?

Yes, but not yet in most clinics. Specialized metagenomic tests can identify bacterial genes that break down drugs-like beta-glucuronidase or azoreductase. These tests are used in research and some specialty centers. They cost $300-$500 and take about 2-3 weeks. While not standard yet, they’re becoming more accessible as doctors recognize their value.

Why do some people have worse side effects from the same drug?

Your gut bacteria play a major role. For example, 25-40% of people taking the chemo drug irinotecan get severe diarrhea because their gut bacteria reactivate a toxic form of the drug. Others don’t have the right bacteria, so they don’t. It’s not about dosage or weight-it’s about your unique microbial makeup.

Should I stop taking antibiotics if I’m on other meds?

Never stop antibiotics without talking to your doctor. But do tell them about all your medications. Antibiotics can alter how your body handles drugs for months. If you’re on heart meds, epilepsy drugs, or chemotherapy, your doctor may need to adjust your dose after a course of antibiotics.

Are there drugs that are safe for everyone, regardless of gut bacteria?

Very few. Most drugs are affected to some degree. Even common painkillers like acetaminophen show microbiome-related metabolism differences. The drugs most affected are those with narrow therapeutic windows-like digoxin, warfarin, and chemotherapy agents. These are the ones where small changes in concentration can be dangerous.

11 Comments

Wow, this changed how I think about my meds. I always thought my body was just broken, but now I realize it’s my gut. I got severe diarrhea on chemo and they blamed me for not drinking enough water. Turns out, my bacteria were turning it into poison. I’m getting a stool test next week.

This is why America needs to stop letting foreigners run our labs. We’ve known this for decades, but now big pharma is cashing in on ‘microbiome testing’ like it’s new. We invented antibiotics. We should be leading this, not outsourcing it to some startup with a $500 DNA kit.

The data presented here is compelling and aligns with recent findings in microbial pharmacometabolomics. The enzyme-specific degradation pathways, particularly beta-glucuronidase-mediated reactivation of irinotecan, are well-documented in murine models and human cohort studies. However, the translational applicability remains limited by inter-individual microbial variability and lack of standardized assay protocols. Further validation in longitudinal clinical trials is warranted before routine clinical adoption.

Let me tell you something - this isn’t just science, it’s liberation. For years I was told I was ‘non-compliant’ because my blood pressure meds didn’t work. Turns out, my gut ate them alive. Now I’m on a new regimen, got my microbiome mapped, and I’m not just surviving - I’m thriving. Stop blaming your body. Start asking what’s living inside it. You’re not broken. You’re just misunderstood.

This is one of the most important pieces of medical insight I’ve read in years. The implications are staggering. We’ve spent decades optimizing drug dosages based on weight, age, liver function - but ignored the trillions of organisms living in our intestines that are literally rewriting the pharmacology of our pills. It’s time we treat the microbiome like a vital organ. Not an afterthought. Not a curiosity. A core component of pharmacokinetics.

HAHAHA this is so american. We have real problems like hunger and pollution but you guys are spending money on poop tests for pills. In India we take one pill and if we feel weird we drink chai and pray. No fancy machines needed. Also your antibiotics are too strong anyway, we use turmeric for everything.

Interesting. But where is the peer-reviewed data on clinical outcomes? This sounds like a marketing campaign disguised as science. Also, why is no one discussing the ethical implications of genetic profiling for drug response? Who owns your microbiome data? And how many people will be denied insurance based on their bacterial profile?

Man I never thought about this. I’ve been on antidepressants for years and always wondered why I felt nothing sometimes. Maybe my gut just ate them. I’m gonna ask my doc about a stool test. No pressure, just curious. Also I’m gonna stop taking probiotics from the grocery store. They’re probably just sugar and dead bacteria anyway.

My grandma took digoxin for 20 years and never had issues. Then she got pneumonia, was on antibiotics for a week, and started getting dizzy. Doc thought it was old age. Turns out her gut bacteria died off and the drug spiked. She’s fine now, dose adjusted. This stuff matters. Ask your doc if your meds might be getting eaten.

Typical overhyped nonsense. 20% of toxic metabolites? So what? Most drugs are toxic by design. You think your ‘microbiome’ is special? Everyone’s got bacteria. This is just pharma trying to sell you another test so they can charge you $500 to tell you what you already know: your body reacts differently than others. Stop paying for buzzwords.

This is beautiful. In India we call this ‘antibiotic ki kami’ - the weakness of antibiotics. We’ve always known that food and gut change how medicine works. My uncle took TB drugs and got sick until he started eating yogurt daily. No science needed, just tradition. But now science is catching up. Keep going. We need this knowledge everywhere.