Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) aren’t just rare skin conditions-they’re medical emergencies that can turn a routine medication into a life-threatening event. Think of them as your body’s extreme, violent overreaction to a drug it shouldn’t have been exposed to. One minute you’re feeling under the weather with a fever and sore throat; the next, your skin starts peeling off in sheets. It’s not a rash. It’s not a burn. It’s a full-thickness collapse of your skin’s outer layer, triggered by your own immune system. And while it’s rare-only 1 to 6 cases per million people each year-it’s deadly. Up to 25% of people with the most severe form, TEN, don’t survive.

How SJS and TEN Are Connected

For decades, doctors treated SJS and TEN as two different diseases. But by the 1990s, the medical world realized they’re part of the same spectrum. The only real difference is how much of your skin is affected. If less than 10% of your body surface area loses its outer skin layer, it’s classified as SJS. Between 10% and 30%, it’s called SJS/TEN overlap. Anything over 30%? That’s Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis-the most dangerous form. The same triggers, the same symptoms, the same life-or-death stakes. The difference is just how far it’s gone.

It’s not just skin deep. Every single person who develops SJS or TEN will have damage to at least two mucous membranes-usually the mouth, eyes, and genitals. You might wake up with a burning throat, eyes stuck shut from crusting, or painful sores in your genital area. These aren’t minor irritations. They’re open wounds that make eating, blinking, and urinating agonizing. And because the skin barrier is gone, your body loses fluids and heat like someone with a major burn. Infection is almost guaranteed without immediate care.

What Triggers These Reactions?

Over 80% of cases are caused by medications. The rest are linked to infections, especially Mycoplasma pneumoniae in kids. But when it comes to drugs, some are far more dangerous than others. Carbamazepine, used for epilepsy and nerve pain, is one of the biggest culprits. So is allopurinol, taken for gout. Sulfonamide antibiotics like Bactrim are also high-risk. Even common painkillers like ibuprofen or naproxen can trigger it, though less often.

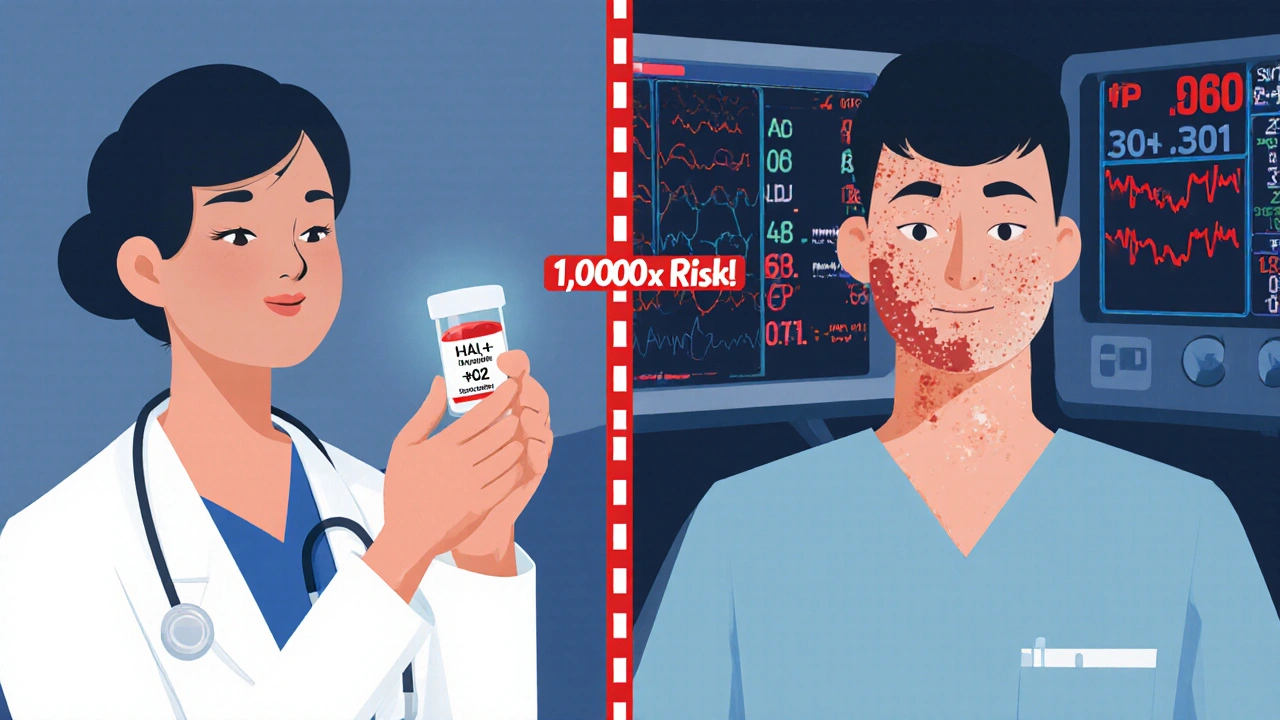

Here’s the scary part: it’s not about how much you take. It’s about your genes. If you carry the HLA-B*15:02 gene variant, your risk of developing SJS/TEN from carbamazepine jumps by 1,000 times. That’s why in places like Taiwan, doctors test patients for this gene before prescribing carbamazepine. Since 2007, that simple blood test has cut SJS/TEN cases by 80%. Similarly, the HLA-B*58:01 gene makes allopurinol far more dangerous. In 2022, the FDA approved a point-of-care test for this gene-results in four hours, not two weeks.

That’s why knowing your family history matters. If someone in your family had a bad reaction to a drug, especially one of these, tell your doctor. Genetic testing isn’t routine everywhere yet, but it should be considered before starting high-risk meds.

The Warning Signs Before It’s Too Late

The first signs of SJS/TEN look like the flu. Fever above 102°F, sore throat, cough, burning eyes, fatigue. You might think it’s just a bad cold or the flu. But within 1 to 3 days, something changes. Red or purple spots appear on your chest or back. They don’t itch. They hurt. They spread fast. Then blisters form. Your skin starts to slough off with the slightest touch-the Nikolsky sign. Rub your skin gently, and the top layer peels away. That’s not normal. That’s a red flag.

And then the mucous membranes start failing. Your mouth feels like it’s full of raw sores. You can’t swallow. Your eyes are swollen shut. You can’t pee without extreme pain. This isn’t a skin problem. It’s a full-body crisis. By the time you see a doctor, the damage is already done. That’s why timing is everything. If you’re on one of those high-risk drugs and you develop these symptoms, stop the medication immediately and go to the ER. Don’t wait. Don’t call your GP. Go to the hospital now.

How Doctors Diagnose It

There’s no single blood test for SJS/TEN. Diagnosis relies on three things: your symptoms, your medication history, and a skin biopsy. The biopsy is the gold standard. Under the microscope, doctors look for full-thickness death of the epidermis-the top layer of skin-with almost no inflammation underneath. That’s the fingerprint of SJS/TEN. It’s what separates it from other skin conditions like staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, which mostly affects children and has a different pattern of skin separation.

Doctors also use the SCORTEN score to predict survival. It looks at seven factors: age over 40, cancer history, heart rate over 120, more than 10% skin loss, high blood sugar, high urea levels, and low bicarbonate. Each factor increases your risk of death. Three factors mean a 35% chance of dying. Five or more? It jumps to 90%. That’s why early hospitalization isn’t optional-it’s survival.

What Happens in the Hospital

If you’re diagnosed with SJS or TEN, you’re not going to a regular ward. You’re going to a burn unit or intensive care. Why? Because your skin is gone. You’re losing fluids, proteins, and heat like a burn victim. You need IV fluids-three to four times more than normal. You need sterile, non-stick dressings. You need pain control that actually works. And you need a team: dermatologists, infectious disease specialists, ophthalmologists, and nurses trained in wound care.

The first rule? Stop every non-essential drug. That includes supplements, vitamins, over-the-counter meds. You’ll need a detailed list of everything you’ve taken in the last 4 weeks. Then, you’ll get tested for the HLA genes linked to your reaction. That’s not just for you-it’s for your family. If you carry the gene, your siblings or children might be at risk too.

Treatment: What Works, What Doesn’t

There’s no magic cure. But some treatments have shown real promise. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was once the go-to, but large studies showed it doesn’t reduce death rates. Steroids? They can help early on, but they also raise your risk of deadly infections. Cyclosporine, an immune suppressor, has been shown in trials to cut mortality from 33% to 12.5%. And etanercept, a drug that blocks a key inflammatory protein (TNF-alpha), has led to zero deaths in small studies when given within 48 hours.

But the most powerful treatment is time-and expert care. Your skin will regenerate, but it takes weeks. Your mucous membranes will heal slowly. Your eyes? They might never fully recover. About half of survivors need lifelong eye drops for dryness. One in four develops corneal scarring. Five percent lose vision. And that’s just the physical damage.

Long-Term Damage You Can’t See

Surviving SJS or TEN doesn’t mean you’re back to normal. Sixty to eighty percent of survivors live with lasting problems. Your skin might be permanently discolored-patches darker or lighter than the rest. Your nails might grow crooked or fall off. Your urethra could scar shut, requiring surgery. Women might develop vaginal adhesions. And your lungs? They can be permanently damaged from the inflammation.

Then there’s the invisible toll. Four out of ten survivors develop PTSD. The pain, the isolation, the fear of dying, the weeks spent in a hospital with strangers touching your raw skin-it changes you. Many can’t return to work. Some can’t look in the mirror. Therapy isn’t optional. It’s essential.

Can It Be Prevented?

Yes. And it’s already happening in places that use genetic screening. If you’re of Asian descent and your doctor wants to prescribe carbamazepine, ask for the HLA-B*15:02 test. If you have gout and they’re suggesting allopurinol, ask about HLA-B*58:01. These tests cost less than $100. The cost of not doing them? Death.

Even without genetic testing, pay attention to your body. If you start feeling unwell after starting a new drug-especially one of the high-risk ones-stop it and get checked. Don’t wait for the skin to peel. The earlier you act, the better your chance.

Doctors are getting better at predicting who’s at risk. Research is moving fast. Trials for drugs that block the granulysin protein-what actually kills your skin cells-are starting in 2024. That could be the first targeted treatment for SJS/TEN. Until then, knowledge is your best defense.

Can Stevens-Johnson Syndrome be cured?

There’s no instant cure for Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, but survival is possible with rapid, expert care. Stopping the triggering medication immediately and getting treatment in a burn or ICU unit dramatically improves outcomes. Skin regenerates over weeks, but recovery often leaves long-term damage. The focus is on supporting the body while it heals, not on reversing the reaction itself.

Is Stevens-Johnson Syndrome contagious?

No, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome is not contagious. It’s an immune reaction to a drug or infection, not an infection itself. You can’t catch it from someone else. But if you’ve had it, your family members might be at risk if they carry the same genetic markers, especially when taking certain medications.

How long does it take to recover from SJS or TEN?

The acute phase lasts 8 to 12 days, but full recovery takes months. Skin regrows in 2 to 4 weeks, but mucosal healing-especially in the eyes and genitals-can take much longer. Many survivors deal with chronic issues like dry eyes, scarring, and pain for years. Psychological recovery can take even longer, with PTSD affecting up to 40% of survivors.

Can you get SJS or TEN more than once?

Yes, but only if you’re re-exposed to the same medication or a closely related one. Once you’ve had SJS or TEN from a drug, you must avoid that drug and similar ones for life. Cross-reactivity is common-especially among antiepileptics and sulfa drugs. Always inform every doctor you see about your history.

Are children at risk for SJS or TEN?

Children can develop SJS or TEN, but it’s less common than in adults. In kids, infections like Mycoplasma pneumoniae are a more frequent trigger than medications. Still, high-risk drugs like carbamazepine and allopurinol can cause it. Genetic screening is less routine in children, so watch for early symptoms after starting new meds.

What should you do if you suspect SJS or TEN?

Stop all non-essential medications immediately. Go to the nearest emergency room. Don’t wait. Call ahead if you can. Bring a list of all drugs you’ve taken in the last 4 weeks. Time is critical-the sooner you get into a specialized unit, the better your chance of survival. Do not try to treat this at home.

6 Comments

Man, this post hit different. I’ve seen people write off skin rashes like they’re just allergies, but this? This is war. Your body turning on you because of a pill you took for a headache. It’s not just medical-it’s existential. We think medicine is safe because it’s prescribed, but sometimes the cure is the monster. And the genetic part? That’s the real kicker. If your DNA’s got a ticking bomb in it, no amount of ‘I’m careful’ matters. We need this info in every doctor’s office, not just after someone’s skin starts peeling. Knowledge shouldn’t be a luxury. It should be mandatory.

So let me get this straight-your doctor gives you carbamazepine like it’s Advil, and if you’re Asian, you might wake up looking like a melted candle? 😅 And we’re still not testing for this universally? I mean, it’s cheaper than a Starbucks run. I get that healthcare’s a mess, but this feels like leaving a loaded gun in a kindergarten. At least in the US we can *ask* for the test… but most people don’t even know it exists. RIP common sense.

Wait so if you take a pill and your skin falls off, you gotta go to the ER? Duh. But why do they even make these drugs if they do that? Can’t they just not make them? My cousin took something and got sick, now she’s all scarred. Why isn’t this on TV? Everyone should know this.

Oh please. This is all Big Pharma’s fault. They knew about the HLA genes for decades but buried it because they make billions off these drugs. The FDA? Complicit. The ‘genetic testing’ they’re pushing now? A distraction. They want you to think it’s your fault for not getting tested-not theirs for not banning the drugs outright. And don’t get me started on how they use ‘rare’ to justify killing people. 1 in a million? That’s still 300 Americans a year. That’s not rare. That’s genocide by prescription. Wake up.

Wow. Just… wow. 😢 I read this whole thing with my jaw on the floor. I had no idea. My uncle survived TEN after a gout med-he lost his vision in one eye and still can’t eat spicy food. I thought he just got ‘bad allergies.’ This needs to be taught in high school. Like, right after sex ed. 🙏 Also, etanercept sounds like a miracle. Hope they fast-track it. Stay safe out there, folks.

So u mean if u take ibuprofen u might die? lol no. i took like 3 of those last week and im fine. this is just fearmongering. also why are they even testing genes? just dont take meds. duh.