Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) isn’t just about fluid-filled sacs in the kidneys. It’s a lifelong genetic condition that quietly reshapes your body over decades. If you have PKD, your kidneys grow larger than normal-not from muscle or fat, but from hundreds, even thousands, of cysts. These cysts don’t disappear. They keep growing. And over time, they push out healthy kidney tissue until your kidneys can’t do their job anymore. About 1 in every 400 to 1,000 people has the most common form, called autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). That’s roughly 600,000 people in the U.S. alone. For many, the first sign isn’t pain or swelling-it’s high blood pressure during a routine check-up.

How PKD Is Passed Down in Families

PKD doesn’t come from diet, lifestyle, or bad luck. It’s written into your DNA. There are two main types, and they work completely differently.

ADPKD is the big one. It makes up over 98% of all PKD cases. You only need one copy of a mutated gene-either PKD1 or PKD2-to get it. If one of your parents has ADPKD, you have a 50% chance of inheriting it. About 90% of cases come from a parent. The other 10%? Those are new mutations. No family history. Just a random error in the egg or sperm that started it all.

The PKD1 gene mutation tends to be harsher. People with this version often see kidney failure by their 50s or 60s. Those with PKD2 usually hold out longer-sometimes into their 70s. But here’s the twist: even people with the same mutation can have wildly different outcomes. One person might need a transplant at 45. Another, with the exact same gene, might keep good kidney function into their 80s. Why? Scientists think other genes, lifestyle, or even random chance play a role. No one knows for sure.

ARPKD is rare. Only about 1 in 20,000 babies are born with it. To get ARPKD, you need two bad copies of the PKHD1 gene-one from each parent. If both parents are carriers (meaning they have one bad copy but no symptoms), each child has a 25% chance of having ARPKD. This version usually shows up right after birth or in early childhood. Babies may have enlarged kidneys, high blood pressure, and liver problems. Many don’t survive past infancy. But some do, and they grow into adults who still need careful monitoring.

What Happens Inside Your Kidneys

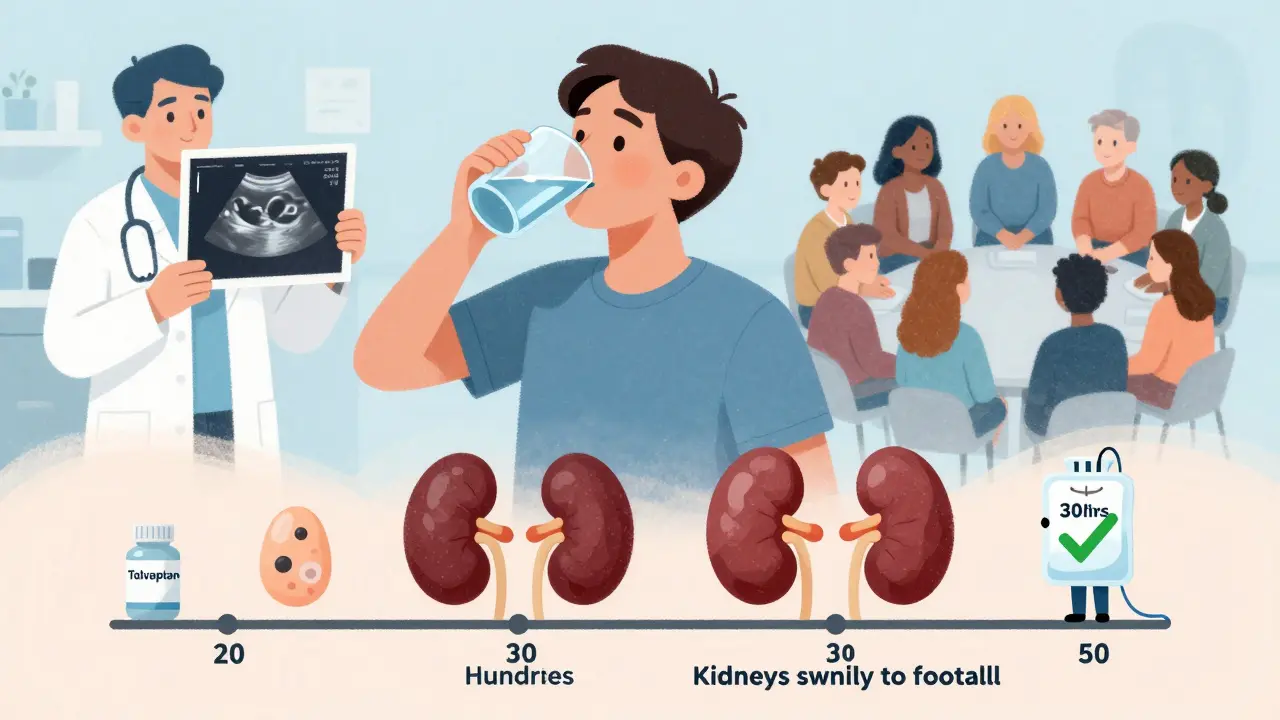

Your kidneys are about the size of a fist. In someone with advanced ADPKD, they can swell to the size of a football. Some patients report their kidneys weighing up to 30 pounds total. That’s not a typo. It’s like your body is slowly filling your kidneys with water balloons.

These cysts start small. Maybe one or two in your 20s. By your 30s or 40s, there could be hundreds. They don’t just sit there. They grow, stretch, and press on healthy tissue. Over time, that tissue dies. Your kidneys lose their ability to filter waste, balance fluids, and control blood pressure.

It’s not just the kidneys. Cysts can form in the liver, pancreas, and even the lining of your brain. That’s why people with PKD often have liver cysts, hernias, or aneurysms in the brain. These aren’t guaranteed, but they’re common enough that doctors screen for them.

When Do Symptoms Show Up?

Many people with ADPKD feel fine for years. That’s why it’s called a silent disease. The first warning sign? High blood pressure. In fact, 89% of ADPKD patients develop hypertension by age 40. That’s not a coincidence. The cysts mess with your kidney’s ability to regulate blood pressure, and high blood pressure then speeds up kidney damage. It’s a vicious cycle.

By age 30 to 40, other symptoms start to creep in:

- Chronic pain in your back or sides (reported by 78% of patients)

- Frequent urinary tract infections

- Blood in your urine

- Increased need to urinate, especially at night

- Kidney stones

Some kids with ADPKD show symptoms before age 10. Others don’t notice anything until they’re 50. There’s no pattern. That’s why family history matters so much. If your parent had PKD, you should get tested-even if you feel fine.

How Doctors Diagnose PKD

If you have a family history and are in your 30s, your doctor might order an ultrasound. That’s the go-to test. It’s cheap, safe, and shows cysts clearly. For someone aged 30-39 with a family history, finding at least 10 cysts in each kidney confirms ADPKD. By age 40, it’s 20 cysts. By 50, it’s 30. The number rises with age.

If the ultrasound is unclear-or if you have no family history but still show symptoms-doctors may use MRI or CT scans. These give a detailed 3D view of the cysts and how much they’ve grown. They’re more expensive but more precise.

Genetic testing is another option. A simple blood or saliva test can check for mutations in PKD1 and PKD2. It costs around $1,200 and is covered by many insurance plans. It’s especially useful if:

- You’re thinking about having kids and want to know your risk

- Your symptoms don’t match the usual pattern

- You’re adopted and don’t know your family history

But here’s the catch: a positive genetic test doesn’t tell you when you’ll need a transplant. It just says you have the gene. So it’s not always helpful for predicting the future.

Managing PKD: What Actually Works

There’s no cure. But there are ways to slow it down. And the earlier you start, the better.

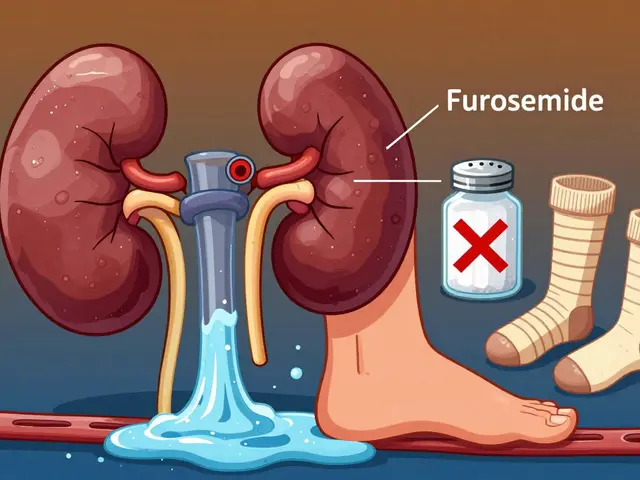

Control your blood pressure. This is the single most important thing you can do. Target: below 130/80 mmHg. Some experts even recommend 110/75 if you can handle it. ACE inhibitors or ARBs are the go-to drugs. They don’t just lower pressure-they also protect kidney tissue. One study showed that tight blood pressure control slowed kidney growth by 14% over five years.

Drink water. A lot. It sounds simple, but staying well-hydrated may slow cyst growth. The theory? Water lowers a hormone called vasopressin, which seems to fuel cyst expansion. Aim for at least 2.5-3 liters a day. Avoid sugary drinks. Caffeine? Limit it. Alcohol? Cut back.

Watch your diet. Eat less salt. Less processed food. More vegetables, lean protein, and whole grains. A high-salt diet raises blood pressure and stresses your kidneys. If you’re already on dialysis, your diet will change again-but that’s a whole other chapter.

Take tolvaptan (Jynarque). This is the only drug approved specifically for ADPKD. It blocks vasopressin and slows kidney shrinkage by about 1.3 mL/min per year. But it’s expensive-around $115,000 a year. And it has side effects: extreme thirst, frequent urination, and liver damage in rare cases. Doctors only prescribe it if your disease is progressing fast-meaning your kidney volume is growing quickly or your eGFR is dropping.

Monitor kidney function. Get your eGFR tested at least once a year. If it drops below 60 mL/min/1.73m², start testing every 3 months. Track your numbers. Know your trend. That’s your early warning system.

What’s Coming Next?

The future of PKD treatment is being built right now. Tolvaptan was the first real breakthrough. But it’s not perfect. Now, researchers are testing new drugs:

- Lixivaptan: A cousin of tolvaptan. Phase 3 trials ended in 2024. Early results look promising.

- Bardoxolone methyl: Originally tested for diabetes-related kidney disease. In PKD patients, it improved kidney function by nearly 5 mL/min over 48 weeks.

- Gene therapies: Still in early testing. The goal? Fix the faulty gene before cysts form.

These aren’t available yet. But they’re close. And they give hope that one day, PKD won’t mean a lifetime of decline.

The Emotional Weight of Living With PKD

Most articles focus on the science. But the real struggle is emotional.

One patient on Reddit said it took seven years and three doctors before they got a correct diagnosis-even though their dad had PKD. That delay means years of uncontrolled blood pressure, unnecessary pain, and fear.

Chronic pain affects 78% of patients. Anxiety about kidney failure hits 63%. Many feel like they’re waiting for a bomb to drop. That’s why support groups matter. The PKD Foundation and American Kidney Fund offer forums, counseling, and peer mentoring. Talking to someone who’s been there? That’s medicine too.

And there are success stories. One man started blood pressure meds at 28. At 45, his kidney function is still at 65%. He’s not cured. But he’s buying time. And that’s everything.

What to Expect Later in Life

By age 70, 75% of people with ADPKD will need dialysis or a transplant. That sounds scary. But transplant success rates are high. A living donor kidney lasts longer than a deceased one. And many patients live 20+ years after transplant.

Wait times vary. In the U.S., it’s 3-5 years on average. But if you have a rare blood type, it could be longer. That’s why planning ahead matters. Talk to your doctor about getting on the transplant list early. And consider asking family members to get tested as potential donors.

Even if you don’t get a transplant, dialysis can keep you alive for decades. It’s not easy. But it’s an option. And it’s not the end.

Is polycystic kidney disease always inherited?

No. About 90% of ADPKD cases are inherited from a parent, but 10% happen from new mutations with no family history. ARPKD requires two inherited mutated genes, so both parents must be carriers. In rare cases, a child can have ARPKD even if neither parent shows symptoms.

Can you have PKD without symptoms?

Yes. Many people with ADPKD feel fine until their 30s or 40s. High blood pressure is often the first clue. That’s why regular check-ups and family history matter. Even if you feel fine, if you have a parent with PKD, you should get tested.

Does drinking water really help with PKD?

Evidence suggests it does. Staying well-hydrated lowers vasopressin, a hormone that may fuel cyst growth. Studies show people who drink 2.5-3 liters of water daily have slower kidney enlargement. Avoid sugary drinks and excessive caffeine-they can raise blood pressure and worsen symptoms.

Is there a cure for PKD?

No cure exists yet. Current treatments focus on slowing progression-mainly by controlling blood pressure and using drugs like tolvaptan. Research into gene therapy and new drugs is ongoing, with several promising candidates in late-stage trials. The goal is to stop cysts before they damage the kidneys.

What’s the difference between ADPKD and ARPKD?

ADPKD is far more common and usually shows up in adulthood. You only need one bad gene copy. ARPKD is rare, appears in infancy or childhood, and requires two bad gene copies. ARPKD often affects the liver too, while ADPKD mainly affects kidneys. Survival rates and progression timelines are very different between the two.

If you have PKD, your life won’t be the same. But it can still be full. With the right care, you can delay kidney failure, manage symptoms, and plan for the future. Knowledge is power. And you’re not alone.

10 Comments