When your kidneys start to fail, they don’t just stop filtering waste-they start losing control over something just as vital: the balance of sodium in your blood. Too little sodium? That’s hyponatremia. Too much? That’s hypernatremia. Both are common, dangerous, and often misunderstood in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD). And here’s the twist: what’s meant to help-like cutting salt or fluids-can actually make things worse.

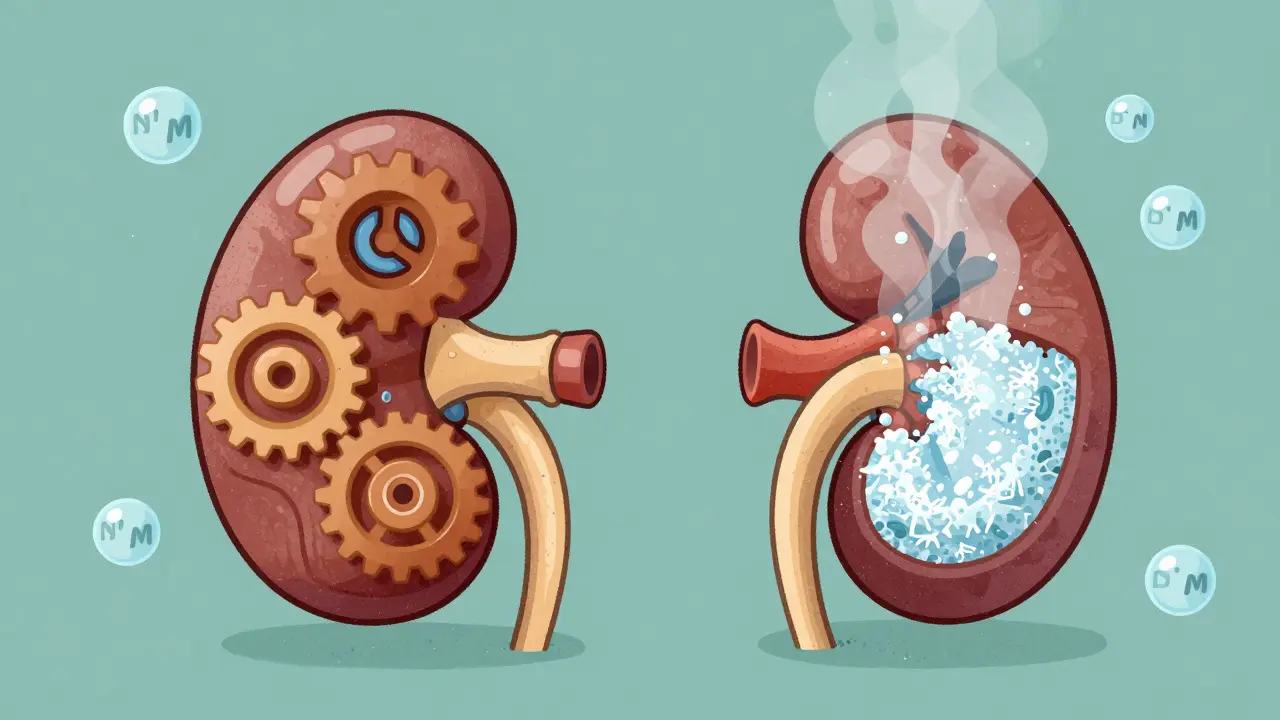

What Happens When Your Kidneys Can’t Handle Sodium

Your kidneys are the body’s main sodium regulators. They decide how much sodium to keep and how much to flush out, based on how much water is around. In healthy people, this system is smooth. But in CKD, it breaks down. As kidney function drops, especially below a GFR of 30 mL/min/1.73m², the kidneys lose their ability to make either very dilute or very concentrated urine. That means they can’t adjust to changes in fluid intake like they used to.This leads to two opposite problems: water builds up and dilutes sodium (hyponatremia), or water leaves and concentrates sodium (hypernatremia). Both are risky. In fact, about 20-25% of people with stage 3-5 CKD develop one of these conditions. And it’s not just about numbers-it’s about what happens to your brain, your heart, and your bones.

Hyponatremia: When Sodium Drops Too Low

Hyponatremia means your blood sodium is below 135 mmol/L. In CKD, it’s the most common sodium disorder, affecting 60-65% of cases. Why? Because your kidneys can’t get rid of extra water. Even if you drink just a little too much, your body holds onto it. This is especially true if you’re on thiazide diuretics-common for high blood pressure-which stop working well once kidney function falls below 30 mL/min/1.73m².But here’s where it gets confusing. Many doctors tell CKD patients to cut salt, protein, and fluids to protect their kidneys. Sounds smart, right? But cutting too much can backfire. A 2023 Japanese study found that patients on very strict low-sodium diets had higher rates of hyponatremia. Why? Because when you reduce solute intake (salt, protein, potassium), your kidneys have less to excrete. And without solutes, they can’t pull water out of your body. Less solute = less water excretion = more dilution = lower sodium.

People with hyponatremia in CKD are at serious risk. Studies show:

- 28% higher chance of falling

- 1.82 times more likely to fracture a bone

- 35% prevalence of osteoporosis (vs. 23% in those with normal sodium)

- 1.94 times higher risk of death

And it’s not just physical. Memory problems, confusion, and slow thinking are common. In hospitals, patients who develop hyponatremia during their stay have a 28% higher chance of dying than those who arrive with it. That’s because the brain adapts slowly to low sodium. Rushing to fix it can cause brain damage.

Hypernatremia: When Sodium Gets Too High

Hypernatremia means your sodium is above 145 mmol/L. It’s less common than hyponatremia in CKD, but just as dangerous. This usually happens when you’re not drinking enough-or can’t drink enough. Elderly patients with CKD are especially vulnerable. They might not feel thirsty, or they might be told to limit fluids because of swelling.In advanced CKD, the kidneys can’t concentrate urine well. So if you’re dehydrated, your body can’t hold onto water. That means sodium gets more concentrated. Symptoms? Dry mouth, confusion, weakness, and in severe cases, seizures or coma.

Correction is tricky. If you fix it too fast, your brain swells. The rule? Don’t drop sodium by more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours. That’s slower than what’s safe for people with healthy kidneys. Many doctors don’t know this. And that’s why hypernatremia in CKD often leads to bad outcomes.

Why Standard Treatments Fail in CKD

Most hospitals treat hyponatremia by giving salt pills or IV fluids. But in CKD, that’s often wrong. Giving salt can make swelling worse. Giving fluids can flood the system. Even vasopressin blockers (vaptans), which work in other patients, are risky in advanced CKD because the kidneys can’t respond.Diuretics are another minefield. Thiazides are out after GFR drops below 30. Loop diuretics (like furosemide) are preferred, but they don’t fix the root problem: your kidneys can’t excrete water. Fluid restriction is the first-line fix-but how much? For early CKD, 1,000-1,500 mL/day is fine. For late-stage CKD, it’s 800-1,000 mL/day. Too much? Risk of hyponatremia. Too little? Risk of hypernatremia.

And then there’s the diet. Patients juggle restrictions: low sodium, low potassium, low protein, low fluid. It’s overwhelming. One study found it takes 3-6 sessions with a renal dietitian just to understand what to eat. And 22% of hyponatremia cases in stage 4-5 CKD come from patients who cut salt too hard, thinking it was safer.

What Works: Real-World Management

The best approach isn’t about one magic fix. It’s about balance. Experts now say:- Don’t assume all hyponatremia is the same. Is it low volume? Normal volume? High volume? Each needs a different plan.

- Fluid restriction must be personalized. A 70-year-old with stage 5 CKD and no urine output needs less than a 55-year-old with stage 3.

- Monitor sodium closely. A new FDA-approved patch (released in March 2023) measures interstitial sodium continuously-no more waiting for blood tests.

- Use multidisciplinary teams. Nephrologists, dietitians, pharmacists, and primary care doctors working together cut hospitalizations by 35%.

And here’s the biggest shift in thinking: not all salt is bad. In advanced CKD, some patients need sodium supplements-4 to 8 grams a day-to avoid salt-wasting syndromes. That’s not a mistake. It’s medicine.

What’s Changing in 2026

New guidelines are coming. The KDIGO Controversies Conference in 2024 will release updated advice, likely pushing for individualized fluid targets based on how much kidney function remains. Research is also looking at the gut-kidney axis-how your intestines might help compensate for failing kidneys in early CKD. That could lead to new treatments down the road.For now, the message is clear: sodium disorders in CKD aren’t just about lab values. They’re about lifestyle, diet, medication, and the body’s ability to adapt. Ignoring the connection between fluid intake, solute load, and kidney function leads to preventable harm.

What You Can Do

If you or someone you care for has CKD:- Ask your doctor: What’s my current GFR? That tells you how much water your kidneys can handle.

- Don’t restrict fluids blindly. If you’re not thirsty and not swelling, you likely don’t need to cut water.

- Track your sodium intake-not just salt, but protein and potassium too. A dietitian can help find the right balance.

- Watch for signs: confusion, dizziness, weakness, nausea, or swelling. These aren’t "just aging." They could be sodium problems.

- Ask about the new sodium patch. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s coming.

CKD is complex. But sodium balance doesn’t have to be a mystery. With the right info, you can avoid the traps and stay healthier longer.

Can drinking too much water cause hyponatremia in kidney disease?

Yes, absolutely. In advanced CKD, the kidneys can’t excrete excess water. Even drinking 1.5 liters a day-something most healthy people do-can lead to hyponatremia if kidney function is below 30 mL/min/1.73m². That’s why fluid limits are tighter in late-stage CKD than in early stages.

Is low-sodium diet always good for CKD patients?

Not always. While high sodium worsens blood pressure and swelling, cutting salt too aggressively can reduce solute excretion, making it harder for the kidneys to get rid of water. This can lead to hyponatremia. Studies show 22% of hyponatremia cases in stage 4-5 CKD come from excessive salt restriction. The goal is balance-not elimination.

Why can’t CKD patients use vaptans for hyponatremia?

Vaptans block vasopressin to help the body pee out water. But in advanced CKD, the kidneys lose their ability to respond to this signal. The drugs don’t work, and they can cause dangerous side effects like liver injury or worsening kidney function. European and U.S. guidelines now recommend against their use in patients with eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73m².

Can hypernatremia be reversed safely in kidney disease?

Yes, but slowly. The rule is to correct sodium by no more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours. Faster correction can cause brain swelling. In CKD, correction must be even more cautious because the brain adapts to high sodium over time. Rehydration should be done with oral water or IV fluids, under close monitoring.

Do all CKD patients need to restrict fluids?

No. Fluid restriction depends on kidney function, urine output, and signs of swelling. Patients with stage 1-2 CKD usually don’t need limits. Those with stage 4-5 and no urine output may need 800-1,000 mL/day. But if you’re not swollen and still making urine, you may be able to drink more. Always check with your care team.

11 Comments

Oh wow, another one of those "doctors are clueless" rants. Let me guess-you also think gluten is a communist plot and vaccines give you autism? People with CKD don't need another amateur guru telling them to ignore medical advice. If your kidneys are failing, you don't get to play nutrition roulette. Drink the water, eat the salt, and pray to the kidney gods? Classic.

It is, indeed, a matter of profound biomedical significance that the human organism, in the context of chronic renal insufficiency, exhibits a systemic dysregulation of electrolytic homeostasis-particularly with respect to sodium ion concentration. The prevailing paradigm of dietary sodium restriction, while intuitively appealing, fails to account for the nuanced interplay between solute load, renal excretory capacity, and osmotic equilibrium. One must not conflate clinical intuition with evidence-based practice.

Hey everyone-this is such an important topic, and I’m so glad someone finally broke it down without the usual medical jargon. I’ve seen too many older patients terrified of water because their doctor said "limit fluids" without explaining why. The truth? If you’re not puffy, not dizzy, and still peeing, you’re probably fine drinking a glass or two more. Your body knows what it needs better than any blanket rule. And that sodium patch? Game-changer. Imagine knowing your levels without a needle every week. We need this everywhere.

Okay, but… have you heard about the secret government program that’s been replacing potassium in salt substitutes with lithium? I read a forum post from a nephrologist in Oregon who said the FDA knew about this since 2019 and covered it up because… well, you know… Big Pharma. And the new patch? It’s not just monitoring sodium-it’s tracking your emotional stress levels too. I swear my cousin’s device started flashing "anxiety spike" right before her dialysis. Coincidence? I think not. 😳

Let’s be real-this whole "balance" thing is just fancy talk for "we don’t know what the hell we’re doing." You think your doc’s gonna give you a personalized fluid plan? Nah. They’re still telling people to drink 2L a day while they’re on hemodialysis three times a week. Meanwhile, some guy in Ohio chugs a gallon of water because he read a blog that said "hydration is healing." Bro, your kidneys are bricks. You don’t need to hydrate like you’re training for the marathon. Stop being a hero. Just listen. Or don’t. I’m not your mom.

Oh my god this is so true i was just telling my cousin in delhi last week she was drinking 3 liters a day and her nephrologist told her to cut it to 1l but she was so scared she only drank 500ml and ended up in the hospital with hypernatremia and they had to give her iv fluids and she cried for 2 hours because she thought she was going to die i mean like why dont doctors just say it like its a scale you dont need to be extreme its like balancing on a tightrope but with your body and also i think the indian diet with all the pickles and chutneys actually helps with solute load i mean we eat so much salt but its natural salt from spices not processed salt so maybe its different idk just saying

I don’t know why this feels so personal. I’ve been managing my stage 4 CKD for 7 years. I used to track every drop of water. I stopped eating salt. I became a monk. And then one day, I felt like a ghost. Weak. Dizzy. Couldn’t think. My sodium was 128. I didn’t know I was dying until my husband screamed at the doctor. I’m not here to lecture. I’m just saying: don’t let fear turn you into a stranger in your own body.

My dad had hyponatremia after a flu. He drank a lot of water thinking it’d help. Turns out, his kidneys couldn’t flush it. He was confused for three days. Scared me half to death. Now? He drinks when he’s thirsty. No limits. No panic. And he’s fine. Sometimes, the simplest thing works.

So i read this whole thing and like… i think the biggest thing is that people think "low sodium" means "no sodium" but its more like "don’t go nuts with the salt shaker"? also i always thought vaptans were magic but turns out they’re just a bad idea for CKD? wow. and that patch? sounds like sci fi but i’m lowkey excited. also i think i spelled "vaptans" wrong lol

Thank you for this exceptionally clear and clinically grounded exposition. The integration of evidence from the 2023 Japanese cohort study, alongside the nuanced discussion of solute-driven water excretion, represents a paradigm shift in the management of electrolyte disorders in advanced CKD. I shall be incorporating these principles into my clinical practice with immediate effect. A truly commendable synthesis.

I’ve been on dialysis for five years. I’ve had hyponatremia. I’ve had hypernatremia. I’ve been told to drink less. I’ve been told to drink more. I’ve been told to eat salt. I’ve been told to avoid salt like it’s poison. And here’s the truth: no one knows. Not really. Not for sure. Not for you. Your doctor’s guess is as good as mine. But here’s what I’ve learned: listen to your body. If you’re not swelling, if you’re not dizzy, if you’re not throwing up… then maybe, just maybe, you’re doing okay. And if you’re scared? Talk to someone who’s been there. Not a blog. Not a guideline. A person. That’s the real medicine.