When a new drug hits the market, the work doesn’t stop just because regulators approved it. In fact, the real test of safety begins after patients start using it in real life - not in controlled clinical trials with a few thousand volunteers, but in millions of people with different health conditions, ages, and lifestyles. This is where post-marketing surveillance comes in. Tracking these studies isn’t optional - it’s a legal requirement, a public health necessity, and one of the most critical parts of keeping patients safe.

Why Post-Marketing Studies Matter

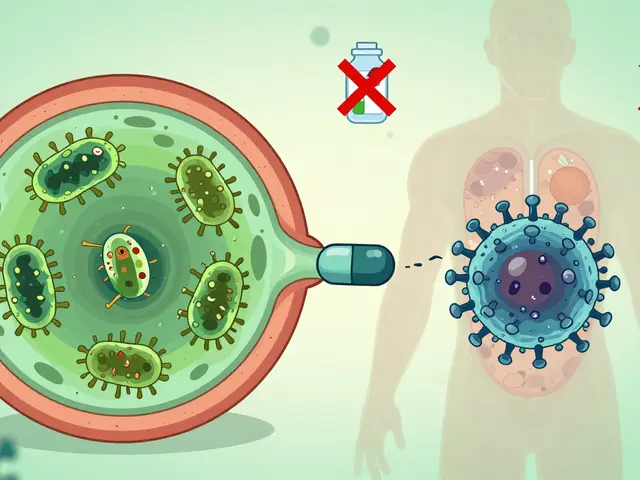

Clinical trials before approval usually involve 5,000 people or fewer. They’re tightly controlled, exclude pregnant women, older adults, and kids, and rarely last longer than a year. But once a drug is sold to the public, it’s used by millions - including people with multiple diseases, those taking other medications, and individuals with genetic differences that affect how their body processes the drug. That’s where hidden risks show up.

For example, studies show that 28% of serious side effects identified after a drug’s release wouldn’t have been caught in trials because elderly patients - who make up 43% of users - were underrepresented. The same goes for rare reactions that only appear after years of use. Without tracking, drugs like Vioxx (withdrawn in 2004) or Zyprexa (with multiple black box warnings) could have caused far more harm.

The Three-Phase System for Tracking

Drug companies don’t just wing it when it comes to post-marketing safety. They follow a strict three-phase process mandated by agencies like the FDA and EMA.

- Planning: Right after approval, companies must submit a detailed safety surveillance plan. This includes how they’ll collect data - through patient surveys, electronic health records, or direct reporting from doctors - and a risk minimization plan that outlines how warnings will appear on packaging, patient guides, and prescriber communications.

- Reporting: Every few months, companies send periodic safety reports to regulators. These include data from spontaneous reports, post-marketing clinical studies, and real-world databases. In the U.S., the FDA’s FAERS (FDA Adverse Event Reporting System) collects over 30 million reports from doctors, patients, and manufacturers. Each report is a clue - a potential signal that something’s wrong.

- Reevaluation: Between 4 and 10 years after launch, companies must re-submit data on quality, effectiveness, and safety. This isn’t a formality. It’s when regulators decide whether to update labels, add new warnings, or even pull the drug off the market.

How Data Gets Tracked: FAERS and Sentinel

Two systems do most of the heavy lifting in the U.S.: FAERS and Sentinel.

FAERS (FDA Adverse Event Reporting System) is the go-to for spontaneous reports. Anyone - a patient, a pharmacist, a nurse - can submit a report if they notice something unusual after taking a drug. In 2022, 63% of all safety actions (like label changes or warning letters) were triggered by these reports. But FAERS has limits. It’s passive. It doesn’t tell you how many people took the drug - just how many reported problems. A spike in reports could mean a real danger… or just more awareness.

That’s where Sentinel (FDA’s active surveillance system) comes in. Sentinel analyzes real-world data from over 300 million Americans - insurance claims, electronic health records, hospital databases. It doesn’t wait for reports. It actively scans for patterns: Did people on Drug X have more kidney failures than expected? Did patients with diabetes on this new medication have higher hospitalization rates?

In 2023, Sentinel expanded its reach by linking EHR data from 24 million people across six major healthcare systems. This gave regulators access to lab results, vital signs, and detailed diagnoses - information FAERS simply can’t provide.

What Happens When a Signal Is Found

Finding a problem is only step one. The real work is deciding what to do about it.

The FDA uses a five-phase signal management process:

- Identification: A pattern emerges - say, a cluster of liver injuries linked to a new diabetes drug.

- Triage: Is this a rare side effect or a major public health risk? Teams prioritize based on how many people are affected and how severe the outcome is.

- Evaluation: Experts cross-check FAERS, Sentinel, published studies, and international databases. They use statistical tools and machine learning to reduce false alarms - false positives dropped from 34% in 2018 to 19% in 2023.

- Action: If the signal is confirmed, regulators act. In 87% of cases between 2018 and 2022, this meant updating the drug’s label. In 9% of cases, a "Dear Health Care Professional" letter was sent. Less than 1% led to withdrawal.

- Communication: The FDA issues a Drug Safety Communication, posts updates quarterly, and publishes findings in peer-reviewed journals. Transparency is key.

The Big Challenges

Despite all the systems in place, tracking post-marketing studies is still a mess in many ways.

One major issue? Delays. Between 2015 and 2022, 72% of FDA-mandated post-approval studies took longer than required. The average completion time was 5.3 years - over twice the 3-year deadline. Why? Recruiting patients across different hospitals, getting data from fragmented systems, and slow approvals for study protocols.

Another problem? Data gaps. Dr. Janet Woodcock, former head of FDA’s drug center, pointed out that Sentinel often lacks clinical details. Insurance claims tell you someone was hospitalized - but not why. Was it the drug? A fall? A missed dose? Without that context, it’s hard to know if the drug is really to blame.

And then there’s the industry side. A 2022 survey found that 68% of drug companies struggled to meet deadlines. Complex rules, different data formats, and lack of standardized tools make it hard to track studies across countries and systems.

How to Do It Right: Best Practices

If you’re responsible for tracking post-marketing studies - whether you’re at a pharma company, a hospital, or a regulatory agency - here’s what works:

- Use automated monitoring: Set up alerts for protocol deviations, missing data, or unusual reporting spikes. Don’t wait for quarterly reviews.

- Build cross-functional teams: Include pharmacovigilance experts, data scientists, clinicians, and regulatory affairs staff. The recommended ratio is one specialist per $500 million in annual product revenue.

- Track the PMSTI: The Post-Marketing Study Timeliness Index measures what percentage of studies finish on time. Aim for 90%+.

- Use distributed data networks: These let you access data from multiple sources without moving it. Study start times dropped from 14.2 months in 2018 to 8.7 months in 2023 thanks to this shift.

What’s Next? The Future of Drug Safety Tracking

The systems are improving - fast.

The FDA’s Sentinel Common Data Model Plus (SCDM+) (a next-generation data framework) is rolling out in 2024. By 2026, it will integrate genomic data with clinical records for 50 million patients. That means we’ll soon know not just if a drug causes liver damage - but which genetic profiles are most at risk.

The European Union is launching an AI-powered signal detection system for EudraVigilance in 2025. The WHO is building a global data-sharing network with 100 countries by 2027. And pilot programs using Large Language Models (LLMs) (AI tools trained on clinical notes) have improved signal detection accuracy by 42% - though they still generate 23% more false positives than traditional methods.

One thing is clear: The future of drug safety isn’t just about collecting more data. It’s about making smarter use of it.

Final Thoughts

Tracking post-marketing studies isn’t paperwork. It’s a lifeline. Every report, every data point, every delayed study - it all adds up to whether someone will live or die after taking a pill. The systems we have now aren’t perfect, but they’re getting better. And for patients, that’s what matters most.

What is the difference between FAERS and Sentinel?

FAERS is a passive database that collects voluntary reports of adverse events from doctors, patients, and manufacturers. It’s great for spotting unusual patterns but doesn’t tell you how many people used the drug. Sentinel is an active system that analyzes real-world data from over 300 million Americans - including insurance claims and electronic health records. It can calculate actual risk rates by comparing users of a drug to non-users, giving a clearer picture of whether a side effect is truly linked to the medication.

Who is required to report adverse events?

Drug manufacturers are legally required to report all adverse events they become aware of. Healthcare professionals and consumers can voluntarily report through systems like FAERS or the Yellow Card system in the UK. In the U.S., manufacturers must submit reports within 15 days for serious events and annually for non-serious ones. Failure to report can result in fines or regulatory action.

How long do post-marketing studies usually take?

The FDA typically requires companies to complete post-marketing studies within 3 years. However, between 2015 and 2022, the median time to completion was 5.3 years. Delays happen due to difficulties in patient recruitment, data access across healthcare systems, and slow regulatory approvals. Only 28% of studies finished on time during that period.

What happens if a drug is found to be unsafe after approval?

Regulators don’t immediately pull the drug. Most often, they update the drug label with stronger warnings, add contraindications, or require special training for prescribers. In 87% of safety actions between 2018 and 2022, this was the outcome. Other actions include sending "Dear Health Care Professional" letters (9%), modifying Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) (3%), or, in rare cases (less than 1%), withdrawing the drug from the market entirely.

Why are elderly patients underrepresented in clinical trials?

Clinical trials often exclude older adults due to concerns about comorbidities, polypharmacy (taking multiple drugs), or perceived complexity in managing their care. But seniors make up over 40% of drug users. This gap means side effects unique to older populations - like increased fall risk, kidney changes, or drug interactions - often go undetected until after approval. Post-marketing studies are critical for catching these risks.

9 Comments